Timeline of Asian Communities in Canada

There are just over 200 years of experience, from the arrival of the first Chinese settlers to building the trading post at Nootka Sound. The timeline below shows a brief glimpse of the breadth of Asian developments, from trading posts to government constitutions.

The timeline examines the settlement of various Asian groups, the discrimination many of them endured in our early ages, historic accomplishments, firsts, biographies, and the gradual alterations by which Canadian society accepted the right and equality of Asian immigrants.

Source - The Canadian Encyclopedia | Historica Canada

Jan. 1, 1788

The first Chinese to settle in Canada were 50 artisans who accompanied Captain John Meares in 1788 to help build a trading post and encourage trade in sea otter pelts between Guangzhou, China and Nootka Sound.

Jan. 1, 1858

In 1858, Chinese immigrants began arriving from San Francisco as gold prospectors in the Fraser River valley, and Barkerville, BC, became the first Chinese community in Canada. By 1860, the Chinese population of Vancouver Island and BC was estimated to be 7,000.

Jan. 1, 1877

The first known immigrant from Japan, Manzo Nagano, settled in Victoria, BC. The first wave of Japanese immigrants, called Issei (first generation), arrived between 1877 and 1928. By 1914, 10,000 people of Japanese ancestry had settled permanently in Canada.

Jan. 1, 1885

Some 15,000 Chinese labourers completed the British Columbia section of the CPR, with more than 600 perishing from dynamite accidents, landslides, rockslides, cave-ins, cases of scurvy because of inadequate food, other maladies, fatigue, drowning, and a lack of medical aid. The death count of Chinese workers over the entire construction period has been estimated to be between 600 and 2,200 workers. Largely because of the trans-Canada railway, Chinese communities developed across the nation.

Jan. 1, 1885

Chinese migrants were obligated to pay a $50 "entry" or "head" tax before being admitted into Canada. The Chinese were the only ethnic group required to pay a tax to enter Canada. By 1903, the head tax was increased to $500; the number of Chinese who paid the fee in the first fiscal year dropped from 4719 to 8.

Jan. 1, 1885

The original draft of the Act gave federal voting rights to some women, but under the final legislation, only men could vote. The Act gives some Reserve First Nations with property qualifications the right to vote but bars Chinese Canadians.

Jan. 1, 1897

The first Sikhs came to Canada at the turn of the 20th century. Some came to Canada as part of the Hong Kong military contingent en route to Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee (1897) and the coronation of Edward VII (1902) and returned to Canada to establish themselves in British Columbia. More than 5,000 South Asians, more than 90 percent of them Sikhs, came to Canada before their immigration was banned in 1908.

Jan. 1, 1902

The federal government appointed a Royal Commission on Chinese and Japanese Immigration, which concluded that the Asians were "unfit for full citizenship ... obnoxious to a free community and dangerous to the state."

Jan. 1, 1907

An order-in-council banned immigration from India and South Asian countries. The population of South Asians in Canada would drop to roughly 2,000, the majority being Sikh. Though wives and children of legal Sikh residents were allowed entry to the country in the 1920s, it would not be until the late 1940s that the policies were changed to allow for full South Asian immigration to Canada.

May 23, 1914

In 1914, 376 people from India aboard the immigrant ship Komagata Maru languished in Vancouver Harbour while Canadian authorities debated what to do with them. Two months later, on 23 July, Canada’s new navy escorted the ship from Canadian waters in action for the first time.

Jan. 1, 1923

An amendment to the 1908 Hayashi-Lemieux agreement reduced the number of male Japanese immigrants to 150 annually. In 1928, the Gentlemen’s Agreement was amended further to include women and children in the count of 150.

March 1, 1941

Everyone of Japanese descent over 16 years old was required by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to register.

Dec. 7, 1941

Immediately following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, 38 Japanese Canadians were arrested as subversives. Twelve weeks after the attack, the federal government used the War Measures Act to order the removal of all Japanese Canadians residing within 160 km of the Pacific Coast. About 21,000 Japanese Canadians in BC, more than 75 percent of whom were Canadian citizens, were fingerprinted, issued identification cards and removed from their homes. More than 8,000 were moved to a temporary detention camp (where women and children were held in a livestock building) at the Pacific National Exhibition in Vancouver.

Jan. 1, 1943

Between 1943 and 1946, the federal government sold all Japanese Canadian-owned property - homes, farms, fishing boats, businesses and personal property - and deducted from the proceeds any social assistance received by the owner while confined and unemployed in a detention camp.

March 14, 1944

Ontario was the first province to respond to social change when it passed the Racial Discrimination Act of 1944. This landmark legislation effectively prohibited the publication and display of any symbol, sign, or notice that expressed ethnic, racial, or religious discrimination. It was followed by other sweeping legislation.

Jan. 1, 1946

In 1946, after the war was over, the government attempted to deport 10,000 Japanese Canadians to Japan but was stopped by a massive public protest from all parts of Canada. Nevertheless, 4,000 Japanese Canadians, more than half of whom were Canadian citizens, were deported to Japan.

Jan. 1, 1947

The Citizenship Act extended the right to vote federally and provincially to Chinese Canadian and South Asian Canadian men and women. However, ignored Indigenous peoples and Japanese Canadians.

Oct. 1, 1967

Prior to 1967, the immigration system relied largely on immigration officers' judgment to determine who should be eligible to enter Canada. Deputy Minister of Immigration Tom Kent established a points system, which assigned points in nine categories, to determine eligibility.

April 30, 1975

The Vietnam War ended with the fall of Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, to Communist forces. In the years that followed, many refugees risked their lives to escape the turbulent political context, human rights violations and rapidly deteriorating living conditions in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. By 1985, Canada had admitted more than 98,000 refugees from these countries.

Since 2015, 30 April has been designated Journey to Freedom Day in commemoration of the perilous journey undertaken by Vietnamese refugees.

Jan. 1, 1978

In 1978, Canada enacted a new Immigration Act that affirmed Canada's commitment to the resettlement of refugees from oppression. Refugees would no longer be admitted to Canada as an exception to immigration regulations. Admission of refugees was now part of Canadian immigration law and regulations.

Nov. 1, 1978

In 1978, Canada accepted 604 refugees from the freighter Hai Hong. The situation of the "boat" people and of Lao, Khmer and Vietnamese "land people" who fled to Thailand grew increasingly severe, and in response, Canada took in 59,970 refugee and designated-class immigrants during the next two years.

Jan. 1, 1980

The first major refugee resettlement program under the new immigration legislation of 1978 came during the early 1980s when Canada led the Western world in its welcome to Southeast Asian refugees and particularly those from Vietnam, often referred to as the "boat people." Many had escaped Vietnam in tiny boats and found themselves confined to refugee camps in Thailand or Hong Kong, awaiting permanent homes.

April 4, 1985

In the Singh Case, the Supreme Court of Canada concluded that a refugee has the right not to "be removed from Canada to a country where his life or his freedom would be threatened."

Aug. 11, 1986

Canadian fishing boats rescued over 150 Sri Lankan refugees off St. Shott’s, NL. The refugees were left in international waters by a smuggler. Without water, food or fuel, the refugees drifted for three days before being spotted. The rescue sparked a debate over how Canada approaches refugees, with some accusing the group of making false claims. In response to a string of similar events, the Mulroney government initiated a reform of the refugee system in 1988.

Oct. 6, 1986

The United Nations awards the people of Canada the Nansen Refugee Award "in recognition of their essential and constant contribution to the cause of refugees within their country and around the world.” Between 1979 and 1981, Canada had accepted more than 60,000 refugees from Vietnam, Cambodge and Laos, many of whom were sponsored by Canadian families and private organizations. It was the first and only time the award was presented to an entire nation.

Sept. 22, 1988

Prime Minister Brian Mulroney acknowledged the wartime wrongs committed against Japanese Canadians and announced compensation for each individual who had been expelled from the coast, was born before 1 April 1949 and was alive at the time of the signing of the agreement. The compensation also provided a community fund to rebuild the infrastructure of the destroyed communities, pardons for those wrongfully convicted of disobeying orders under the War Measures Act, Canadian citizenship for those wrongfully deported to Japan and their descendants and funding for a Canadian Race Relations Foundation.

Nov. 8, 1988

Author Michael Ondaatje was invested as an Officer of the Order of Canada. The Sri Lankan-born highly acclaimed author emigrated from Sri Lanka and came to Canada through England in 1962. He became a Canadian citizen in 1965. Perhaps his most well-known work, The English Patient (1992) was awarded the Governor General's Award for fiction in 1992, and earned Ondaatje a share of the prestigious Booker Prize, the first ever awarded to a Canadian. A 1996 film version of the novel won nine Academy Awards.

Sept. 17, 1998

Vivienne Poy became the first Canadian of Asian descent appointed to the Senate. A historian, entrepreneur, and fashion designer, Poy sponsored the Famous Five monument in Calgary and was instrumental in designation May as Asian Heritage Month.

Oct. 7, 1999

Adrienne Clarkson took office as Canada’s governor general. Prime Minister Jean Chrétien’s appointment of Clarkson marked several "firsts" in the selection of Canada's governor general: she was the first without a military background and the first non-white Canadian to be appointed to the vice-regal position.

Jan. 1, 2005

Filmmaker Deepa Mehta released the final film of her elements trilogy with 2005’s Water. The story of socially marginalized widows who are ostracized in conservative parts of India went through a series of delays as violent protesters threatened Mehta's life and destroyed film sets in the holy city of Varanasi, where "widow houses" can still be found.

Jan. 20, 2005

Norman Kwong succeeded Lois Hole as Alberta's 16th lieutenant governor, the first Chinese Canadian to hold the position in Alberta.

June 22, 2006

Under much community pressure, Prime Minister Stephen Harper offered an apology to the Chinese community for the implementation of the head tax, which had been originally introduced in 1885. An official directive made in Parliament ordered compensation for the head tax of approximately $20,000 to be paid to survivors or their spouses.

April 23, 2015

The Parliament of Canada passed the Journey to Freedom Day Act, establishing 30 April as a national day of commemoration of the exodus of Vietnamese refugees and their acceptance in Canada after the fall of Saigon and the end of the Vietnam War.

May 18, 2016

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau formally apologized for the Komagata Maru incident before the House of Commons. In 1914, a chartered ship carrying Punjabis who sought a better life in Canada was denied entry at the Port of Vancouver. A dramatic challenge to Canada’s former practice of excluding immigrants from India ensued. The passengers were finally turned away after a long legal ordeal, only to face a deadly conflict with police upon their return to India.

Asian Canadians You Should Know

It is an opportunity to remember, celebrate, and educate future generations about the inspirational role Asian communities have played and continue to play in communities across the country.

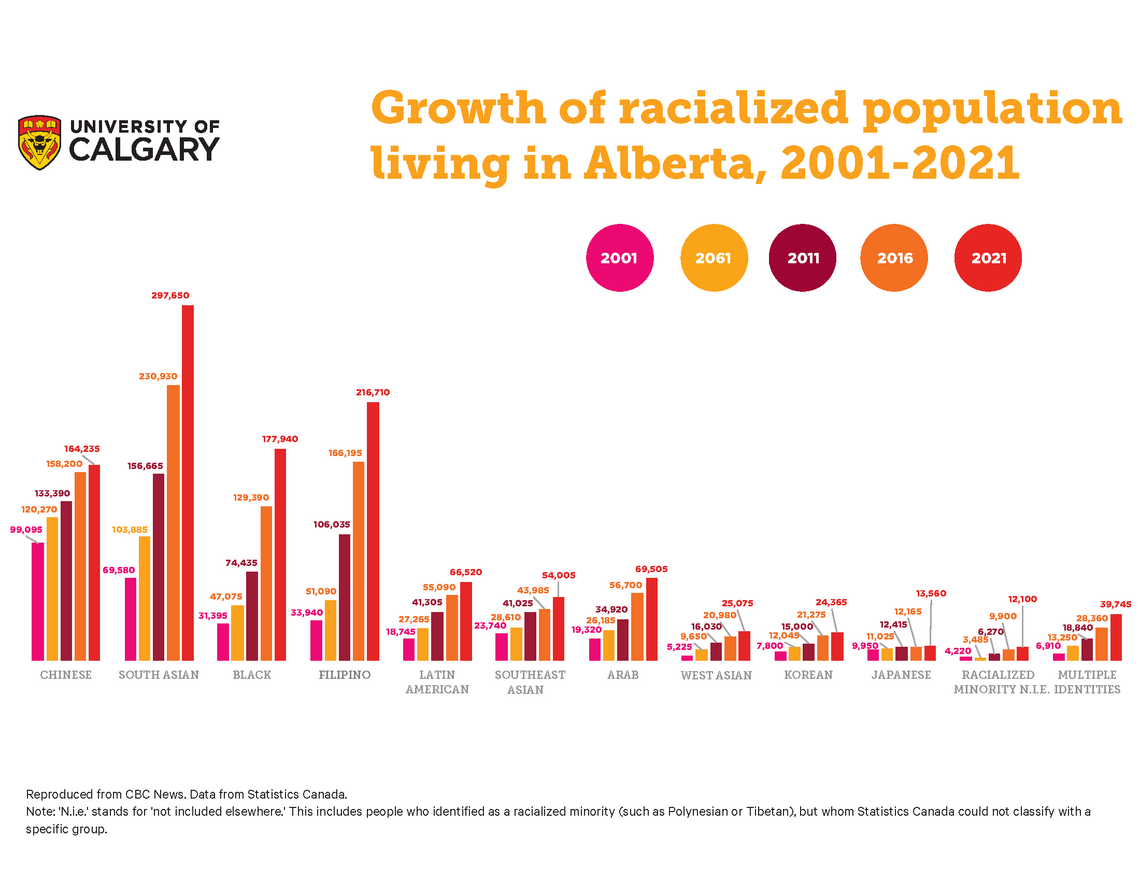

In 2016, Asian countries accounted for seven of the top ten countries of birth of recent immigrants: the Philippines, India, China, Iran, Pakistan, Syria and South Korea.

Asia has remained the top source continent for immigrants in recent years. From 2017 to 2019, 63.5% of newcomers to Canada were born in Asia (including the Middle East).

Sources

Asian Ethnic Groups

Three of the most reported Asian origins in the whole Canadian population were Chinese (close to 1.8 million), East Indian (approximately 1.4 million) and Filipino (837,130). These three were especially common Asian origins for first and second-generation Canadians. Chinese, Lebanese, and Japanese were the most common Asian origins.

- Central Asians - Afghani, Armenian, Azerbaijani, Georgians, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Mongolian, Tajik, Turkmen, Uzbek

- East Asians - Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Okinawan, Taiwanese, Tibetan

- Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders - Carolinian, Chamorro, Chuukese, Fijian, Guamanian, Hawaiian, Kosraean, Marshallese, Native Hawaiian, Niuean, Palauan, Pohnpeian, Papua New Guinean, Samoan, Tokelauan, Tongan, Yapese

- Southeast Asians - Bruneian, Burmese, Cambodian, Filipino, Hmong, Indonesian, Laotian, Malaysian, Mien, Singaporean, Timorese, Thai, Vietnamese

- South Asians - Bangladeshi, Bhutanese, Indian, Maldivians, Nepali, Pakistani, Sri Lankan

- West Asians - Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey (straddles Europe and Asia), United Arab Emirates and Yemen - Most people from this region do not self-identify as West Asians but rather the Middle East.

Source

Filipino Students' Association | University of Calgary

The University of Calgary Filipino Students’ Association (UCFSA) is a social club sanctioned by the Student’s Union (U of C) in 1992. Our goal is to provide its members and the community with a taste of Filipino culture. Our motto is, “Ang hindi marunong lumingon sa pinanggalingan ay hindi makarating sa paroroonan,” which means He who does not look back to his roots will not reach his destination.

With this in mind, the UCFSA strives to help its members realize the best aspects of being Filipino-Canadians while engaging various people and reaching out to the community. With many active members and alumni throughout the community, the UCFSA is the perfect way to meet new people and have fun in a welcoming environment while learning more about Filipino culture.

Chinese Students and Scholars Association

In Calgary, Alberta, UCCSSA has closely collaborated with local and international companies. We also collaborate with the University of Calgary’s International Department, community groups, and other student organizations.

Our association is active year-round; however, the majority of activities will take place from September to April, which is the fall and winter academic semesters. Our executives meet weekly to organize events and meet with our student community.

U of C CSSA aims to enhance the overall university experience for students and introduce the modern and traditional Chinese culture to other communities in and around Calgary. We also work towards developing acquaintanceships and fellowships through hosting events and providing prolonged support to our students and the local communities.

Hong Kong Students' Association

The Hong Kong Students’ Association (HKSA) was established in 1993. We are open to all students and community members. The goal of HKSA is to promote cultural diversity and understanding both at the university and in the community. We also aim to provide academic aid, services for students, and volunteer opportunities and raise Hong Kong and Chinese cultural awareness for the students at the University of Calgary. To achieve this, HKSA holds various group functions throughout the year.

Asian Heritage Foundation Background

As the largest pan-Asian organization in Alberta, the Asian Heritage Foundation supports and develops the community through two key objectives:

- Fostering awareness of the participation and contributions of Asian Canadians

- Raising awareness and addressing issues impacting Asian communities through advocacy, mainstreaming initiatives, policy, and education.

AHF will continue to promote unity and cooperation among Asian communities and between the broader citizenry of Calgary to develop relationships that will lead and drive future initiatives - learn more!

Source - Asian Heritage Foundation

Asian Communities in Canada

Take a quiz to test your knowledge about the immigration history, traditions and key figures of Asian cultures that are part of Canada.

This quiz is made available by The Canadian Encyclopedia | Historica Canada

Featured Publications

Vivek Shraya is a seven-time Lambda Literary Award finalist, a Pride Toronto Grand Marshal and has been a brand ambassador for MAC Cosmetics and Pantene. She is a director on the board of the Tegan and Sara Foundation, an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Calgary, and is currently adapting her debut play, How to Fail as a Popstar, for television with the support of CBC.

Source - vivekshraya.com

Pallavi Banerjee is an Associate Professor of Sociology at University of Calgary. She directs the Critical Gender, Intersectionality and Migration Research Group at the University of Calgary, and her research is supported by Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), Canada and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC).

Source - NYU Press

Larissa Lai holds a Canada Research Chair in Creative Writing at the University of Calgary, where she directs the Insurgent Architects' House for Creative Writings and is the author of three novels, The Tiger Flu (Lambda Literary Award winner), Salt Fish Girl, and When Fox is a Thousand, and three poetry books, Sybil Unrest (with Rita Wong), Automaton Biographies (shortlisted for the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize), and Iron Goddess of Mercy. She is also the winner of Lambda Literary's Jim Duggins Outstanding Mid-Career Novelists Prize and an Astraea Foundation Award. Her latest novel, The Lost Century, will be published in 2022.

Source - larissalai.com

Abdolmohammad Kazemipur is a Professor of Sociology and the Chair of Ethnic Studies at the University of Calgary. In Sacred as Secular, Abdolmohammad Kazemipur attempts to debunk the flawed notions of Muslim exceptionalism by looking at religious trends in Iran since 1979.

Drawing on a wide range of data and sources, including national social attitudes surveys collected since the 1970s, he examines developments in the spheres of politics and governance, schools and seminaries, contemporary philosophy, and the self-expressed beliefs and behaviours of Iranian men, women, and youth.

Source - McGill-Queen's University Press

Teresa Wong is a Canadian Writer-in-Residence Teresa Wong at the University of Calgary. Dear Scarlet: The Story of my Postpartum Depression (2019)is her first book and is an unflinchingly honest graphic memoir, a breakout success which became a finalist for the City of Calgary W.O. Mitchell Book Prize while being longlisted for CBC Canada Reads 2020 and reviewed enthusiastically in the New York Times and the Paris Review.

Source - Arsenal Pulp Press

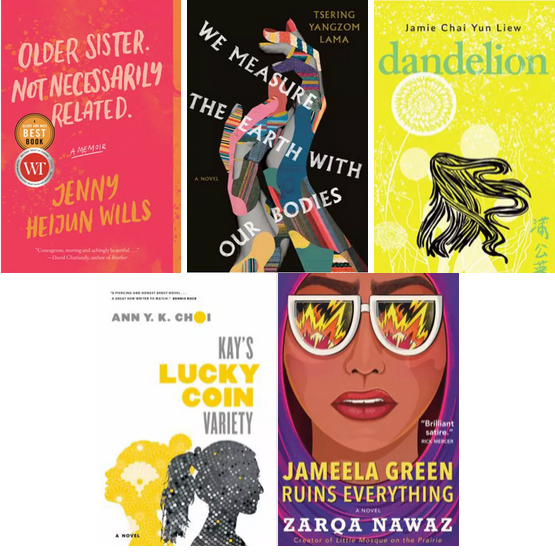

Books by and on Asian Canadians

A curated book list from various authors, including novels, memoirs and historical accounts. You can find stories that will foster joy, compassion, resilience, and understanding.

Films by and on Asian Canadians

This selection highlights many of the accomplishments of Asian Canadians who, throughout Canadian history, have made a rich and diverse nation through film.

Podcasts by and on Asian Canadians

Listen to podcasts from hosts and guests with a wide range of experiences about Canada from Asian communities.