March 29, 2019

Children get bad migraines, too

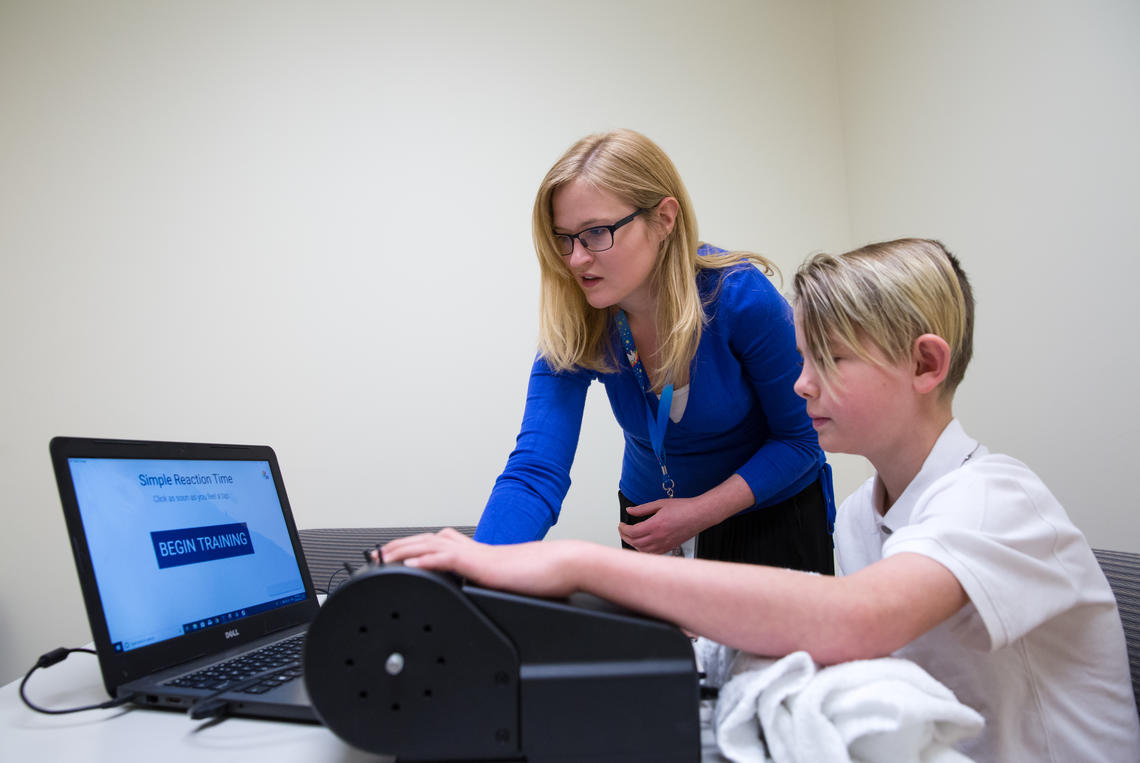

Heather Oosterhuis enrolled her son Mason Corson, age 10, in a study led by Ashley Harris.

Riley Brandt, University of Calgary

Heather Oosterhuis never heard of a child having migraines, until her own child started having them. Mason, age 10, began showing symptoms when he was very young. Oosterhuis noticed something was wrong when her son, as a toddler, would withdraw occasionally without a reason. “We could see that at times something was going on in his head to make him stop playing and go seek a quiet place,” says Oosterhuis.

The triggers for the migraines became more evident when Mason was starting school. They hit once a month. Usually chinook winds or over-exertion would trigger the episodes. Mason would experience nausea and extreme fatigue for an hour. Mason’s mom says the intense pains in his head are something he has learned to tolerate.

“It really knocks him out for a few hours,” says Oosterhuis. “He’ll get a twinge in his head, his face will go pale, large circles of dark purple will appear under his eyes and he’ll be seeing black spots — then you know it’s coming.”

Migraines often continue into adulthood

The Oosterhuis family decided to participate in a research study at the Alberta Children’s Hospital to better understand what was happening to Mason. The study, called the Understanding Paediatric Migraine Study, is run by Dr. Ashley Harris, PhD, a neuroscientist and assistant professor in the Cumming School of Medicine’s (CSM) Department of Radiology, and a member of the CSM’s Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute and Hotchkiss Brain Institute.

“We currently have limited knowledge about what in the brain underlies migraine, with even less information known about childhood migraine specifically,” says Harris. “As often occurs, much of our knowledge about paediatric migraine is assumed from adult migraine, despite known differences in symptom presentation, and responses to therapy.”

It’s estimated that about one in 25 children suffer from migraines, according to the American Migraine Foundation. In addition to their debilitating effects, children with migraines regularly suffer from related symptoms such as anxiety, depression, sleep and eating disorders. Some children are so affected by migraines that their school work and social life can suffer. So too, the families can carry an increased burden of anxiety and stress.

About half of young children outgrow migraines in adolescence. But for the other half of the population, these migraines intensify. Evidence shows that early intervention can increase the remission rate of migraines and even prevent advancement into adulthood.

The study, called Understanding Paediatric Migraine, is led by Ashley Harris.

Riley Brandt, University of Calgary

Enrolling kids with migraines into study

The Understanding Paediatric Migraine Study is enrolling children aged seven to 16 with physician-diagnosed migraines. Harris says the study uses tactile-sensory and imaging measures to investigate the neurobiology of migraine in children.

During the visit, the participants complete a series of questionnaires about their migraine pain and how it effects their life. They then perform the tactile-sensory task set up like a computer game, which most kids find fun. The kids will also have a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan in which the research team will collect imaging data about chemicals in the brain thought to be related to a migraine. The team will look at brain connections, as well.

“Ultimately, our research team is trying to determine the differences between the brains of children who have migraine and children who do not, by looking at how the brain processes sensory (touch) information and looking for differences in brain chemistry and function with MRI," Harris says. Increasing an understanding of the neurochemistry of childhood migraine is a crucial first step in the development of earlier, improved diagnoses and targets for interventions and treatments.

Mystery of migraines

Mason is excited to be part of the study. He thinks it’s cool that researchers are interested in his brain. For his mom Heather, she simply wants to know why Mason has migraines at all, as the family has no history of them. “It’s a complete mystery why Mason has them, we’d like to better understand so that we could help him and other children with this condition.”

For more information on participating in this study, please email harrislabgroup@ucalgary.ca. Find general information on paediatric migraine.

The paediatric migraine research is supported under the program Child and Adolescent Imaging Research (CAIR) at the Alberta Children’s Hospital and the University of Calgary, funded by community donations through the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation. Harris also receives funding through the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI) and the Sick Kids CIHR IHDCYH New Investigator Grant.

Led by the Hotchkiss Brain Institute, Brain and Mental Health is one of six research strategies guiding the University of Calgary toward its Eyes High goals. The strategy provides a unifying direction for brain and mental health research at the university and positions researchers to unlock new discoveries and treatments for brain health in our community.

Study participants will perform tactile-sensory tasks and undergo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Riley Brandt, University of Calgary