| UNIT DESCRIPTION |

| CHOOSING A TOPIC |

| PRELIMINARY RESEARCH |

| DEVELOPING YOUR QUESTION |

| AVOIDING PLAGARISM |

| UNDERSTANDING CITATION |

| REFERENCE LIST |

CHOOSING A TOPIC

- Topic Pyramids

- Research Assignment Parameters

- Identifying Interests

- How to Brainstorm

- Controversy

- Availability of Sources

To write a good research paper, you must begin with a good research question.

- A good research question is appropriate to the assignment.

- The question should genuinely interest you.

- The question addresses an issue of controversy in the field.

- There are sufficient and appropriate sources available to adequately consider and answer the question.

Topic Pyramids

Developing a question begins with choosing a preliminary topic. A preliminary topic is simply a place to begin researching. No matter what your preliminary topic is, it will fit into a topic pyramid that begins with general topics and narrows eventually to specific questions. The more general your preliminary topic is, the closer it will be to the overarching topic of the class.

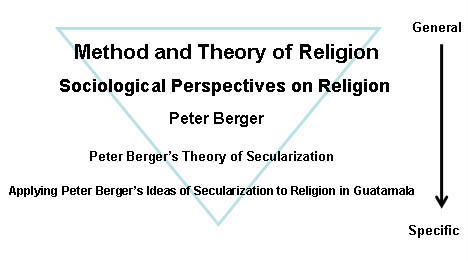

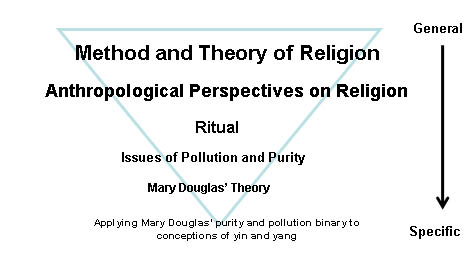

The following are two inverted triangles or "topic pyramids" that illustrate a hierarchy of categories that proceeds from general to specific.

The broadest level of the topic pyramid will be set for you by the content of the course. How far down the pyramid your initial topic falls often depends on how familiar you already were with the area you have chosen for research. If you had a general interest in sociology, but no specific ideas on what you wanted to research, you might begin at the top of the pyramid and browse through books on the sociology of religion. If you were interested in the ritual theory of Mary Douglas, you might begin by searching for sources by and about Mary Douglas.

Keep in mind that the scope of the pyramid varies. Depending on your research requirements, you may have to go narrower or broader than these examples suggest.

How you approach your preliminary research will depend on how specific or general your preliminary topic is. No matter where your topic falls on the pyramid of generality, remember that you are not trying to come up with a perfect question yet but simply a place to start. Even if your preliminary topic is very narrow already, you may find that your final research question changes drastically from your original idea.

TIP - Be flexible with your topic and pay attention to what is coming up in your research. Sometimes a particular idea is not working but another seems to come up everywhere or a different approach to your topic seems more interesting or more appropriate. As long as it fits the criteria of a good topic, go with the new idea or approach!

Though the four characteristics of a good question presented above may appear to be steps in the process of developing a preliminary topic, it is rarely a linear step-by-step process. Sometimes different aspects of research will develop at the same time or certain “steps” will be returned to again and again. Find the approach that works best for you.

Research Assignment Parameters

You will already have a general research area set by the course itself. For example, if you are in a class on Judaism, your research will have to be relevant to Judaism. This is not the only limit on your topic that is set in advance. The amount of material that you will be able to cover effectively will be determined in part by the length of the assignment required. The type of assignment may also affect your choice of topic, depending on whether what is required is an essay, an oral presentation, or a multimedia presentation. It is always necessary first to examine the assignment carefully so you have a clear idea of its parameters. Ask yourself the following questions:

- What are the content parameters?

The possible topic of your assignment is always set at the very least by the content of the course you are taking. Sometimes your professor will further narrow the topics allowable for your research.- What is the required length of the assignment?

When the required length of an assignment is given in pages, this always means typed and double-spaced. There are between 250 to 300 words per page. If you are given an assignment of 2500 words, that is an eight to ten page paper.- What are source requirements?

How many sources do you need? Are primary and/or secondary sources required? Do you need current sources? How current?- When is your deadline?

Keep these limits in mind when developing your question.

TIP - It is important to remember that religious studies is done from a non-confessional perspective. This means that papers from a confessional standpoint are not considered academically acceptable. A confessional perspective is one taken from within a particular faith community, i.e. it is a religious rather than a religious studies perspective. This is essential to keep in mind when developing your research question.

Identifying Interests

It is important to select a topic that interests you. If you are actually interested in what you are researching you will find it much easier to stay motivated and your final paper will be much more interesting for others to read. Think about writing a research paper not as a chore to do to get the marks you want, but as an opportunity to explore your own interests beyond what is covered in class.

Some people already will have an idea of what they want to research when they register in a course; for others coming up with an initial idea is the hardest part of the task. Though this can be accomplished by reading the Encyclopedia of Religion from cover to cover, there are many more effective and efficient ways to begin. The following general starting points should help you to come up with some ideas that genuinely interest you.

Previous Interests

Ask yourself what previous interests you could explore in the context of the class. What books do you read for interest and what topics do you like to discuss? For example, if you are always finding yourself in the women’s section of a bookstore and discussing women’s issues with friends, look for issues pertinent to women within the limits of the assigned topic. If you are attracted to films and books about India, try to come up with a topic in line with that interest.Classes

Listen for ideas that interest you in class, including classes other than the one the paper is for. You may see connections that you would like to pursue. If you are fascinated by your ritual studies class you might want to analyze a Taoist ritual for your Chinese religions class.Textbooks

Scan tables of contents, indexes, and bibliographies in your textbooks. If your religious experience class used Psychology of Religion: Classic and Contemporary Views[1], in the table of contents you might find “Chapter Four: Religion in the Laboratory” interesting, especially the subheadings on the experimental studies of prayer. In the first half of the index alone you will find the following topics, all of which could be pertinent to the class:

- Aggression – religious support of

- Bach’s Mass in B Minor

- Compassion

- Dance

- Environmental concern and Christian conservatism

Even if a topic is mentioned only once, it may be a great starting place for deeper examination.

In the bibliography of the same book, your curiosity may be piqued by the title of Zaleski’s book, Otherworld Journeys; Accounts of Near-Death Experience in Medieval and Modern Times or Zaehner’s Zen, Drugs and Mysticism. Either could be a starting point for you in developing a topic.

Brainstorm

Use brainstorming techniques to come up with as many ideas as possible. Remember, the more ideas you have the more likely you will find one worth developing. For tips on brainstorming, see below.Wait, watch and listen

Sometimes the best way to develop ideas is to let them come to you unbidden. Keep a notebook handy to jot down ideas when they occur to you; you may find that the best ideas come to you while riding the bus, taking your morning shower, or eating lunch.This process will take time so start early in the term! As soon as you know you have an assignment due, start recording any ideas you have, no matter how unfeasible they may seem. Just as with brainstorming, many of your ideas will be discarded but the more you write down, the more likely you will have one or two that will lead to a great question.

TIP - Keeping an ongoing list of interests can be helpful for future assignments.

How To Brainstorm

Brainstorming is a process intended to develop as many ideas as possible in a set amount of time. The key to brainstorming is allowing yourself to write down even your worst ideas without judging yourself or the ideas. Before you begin brainstorming, you should expect 90% of your ideas to be unusable.

- Commit to a certain amount of time (5-15 minutes).

- Write down everything that comes into your head, no matter how outlandish. Crazy ideas often get the creative juice flowing, which can lead to some great research topics and questions. Sometimes, recruiting others to brainstorm with you will help you set off in new directions.

- Don’t stop writing for the set amount of time.

- Don’t start judging or second-guessing yourself. Write everything down that comes into your mind.

- Once you have finished your allotted time set the paper aside for a while.

- Come back to your ideas and select the most promising ones.

Keep your list until your research paper is done; you may want to go back to it.

Mind mapping

For people who work visually, mind mapping can be a useful brainstorming technique. Mind mapping works in much the same way as brainstorming but your ideas are recorded in a visual manner. If this appeals to you, there are many resources for mind mapping. Check out Tony Buzan’s book Use Your Head or look up mind mapping on the web. One Web site is http://www.jcu.edu.au/studying/services/studyskills/mindmap/.Once you have come up with an area of interest that is appropriate to your assignment you will have to ask if your topic is controversial and if there are enough sources to answer your question effectively.

Controversy

To develop a good question it is necessary to identify a controversial issue about your topic. This does not mean that discussion of your topic will set off nasty arguments at parties, but that conceivably more than one answer might be given to the question, more than one point of view or interpretation could be argued convincingly. If there is only one thesis statement about your topic on which all reasonable people would agree, then you have failed to find a true controversy. On the other hand, if there is more than one possible answer to your question, then you have found a controversial topic. Your job will be to decide which answer is most convincing and to convince others of your judgment.

Controversy is linked to interpretation and evaluation. If a topic is not interpreted or evaluated but simply presented, then you do not have a good starting point for an academic paper. A good rule of thumb is that if you can find more than one point of view expressed by reputable scholars on your topic, then you have found a controversy worthy of examination and exploration in a research paper.

Thesis Statements

Those diverse points of view that signal controversy are expressed in scholarly literature as thesis statements. To put it simply, a thesis is the answer to a research question. You will need a thesis statement for your paper. Once you have a thesis, you will then write your essay with the intention of clearly expressing and supporting that thesis in order to convince your audience of its validity. Most research papers at the undergraduate level have only one thesis. You might consider and reject numerous judgments in one paper, but in the end it should be clear how you have answered the question you have posed.

Your thesis is the answer to your research question, which you have arrived at by doing research. Your answer should be clearly articulated in one concise thesis statement that appears in the introductory section of your essay.

Look for controversy by:

- Paying attention to what topics your professors emphasize.

If your professor always returns to the beginnings of Christianity in your New Religious Movements Class, perhaps that is a topic worth exploring.- Listening to debates both inside and outside of class.

Debates tend to develop around controversial topics. If the class cannot resolve a debate about the intersection of politics and religion in your Islam and the Modern World class, consider developing a question in this area.- Browsing academic journals.

Once you know how to find journals, browse through a journal in your general area to find what debates are currently in progress. One of the easiest ways to do this is to find responses to past articles; this immediately indicates a point or argument that is controversial.EXAMPLE

The role of religion in public school systems is a subject of considerable debate and controversy in North America today. Scholarly and public opinion are divided on this issue, with some in favour and others against the curricular inclusion and implementation of religious studies in public classrooms. There are compelling arguments from all sides of the debate, and the issue has received an enormous amount of media attention in recent years. Becoming familiar with both past and present literature on the subject will help you to develop your own research question and thesis statement on the basis of what you have read. Consider the following journal articles retrieved from ATLA and “Google Scholar” searches:

Barnes, Philip L. “Ninian Smart and the Phenomenological Approach to Religious Education.” Religion,ul 30.4 (2000): 315-332.

Boyer, Ernst. “Teaching Religion in the Public Schools and Elsewhere.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 60.3 (1992): 515-524.

Fraser, James W. Between Church and State: Religion and Public Education in a Multicultural America . New York : St. Martin ’s Press, 1999.

Sweet, Lois. God in the Classroom: the Controversial Issue of Religion in Canada's Schools . Toronto : McClelland & Stewart, 1997.

Thompson, Penny. “Critical Confessionalism for Teaching Religion in Schools: A UK Case Study.” Journal of Christian Education 46.2 (2003): 5-16.

Note: Although it is important to familiarize yourself with both scholarly and non-scholarly discussions on a particular issue, your paper should use material only from academic sources (e.g. peer-reviewed journals).

Availability of Sources

Once you have an idea for a research question, you will have to make sure that there are enough sources available to write a paper on that topic. Units 2, 3 and 4 of this Workbook will give you intensive instruction in effective search techniques.

There are no hard and fast rules for how many sources are considered sufficient as assignments are so varied. If your assignment were to analyze “Language, Epistemology, and Mysticism” by Steven T. Katz[2], his article might be your only source or it may be necessary to consult secondary literature on this important essay. In most circumstances, you will need multiple sources, including both primary and secondary sources.

Be particularly aware of the currency of the secondary sources you are using to analyze your topic; make sure they reflect current scholarship and are not all from the 1950’s. If there is no recent secondary literature available, you probably will want to modify your topic to reflect a more current issue.

|

TIP - If the topic or research project that you develop is unusual, it is advisable to talk to your instructor and get approval, even if it is not required, before getting too far into your research. 'Unusual research' includes a project in which your experience acts as a primary source or for which you want to do interviews or field research. If you are using human subjects in any way in your research, it is necessary to seek ethics approval before proceeding.

Click here to continue to the next section

Endnotes

[1] David M. Wulff, Psychology of Religion: Classic and Contemporary Views (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1991).

[2] Steven T. Katz, “Language, Epistemology, and Mysticism,” Mysticism and Philosophical Analysis, ed. Steven T. Katz (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978) 22-74.