Hope for adults with OCD

Imagine having a thought running repeatedly through your mind — one that you cannot block out, one that pushes you to perform rituals like excessively washing your hands or showering for hours at a time. Now imagine how this might impact your relationships, and your ability to concentrate at school or at work. This is a reality for many people living with obsessive-compulsive disorder, or OCD.

OCD is a common, chronic and long-lasting disorder causing a person to have uncontrollable, recurring thoughts or behaviours that they feel the urge to repeat over and over. According to the World Health Organization, OCD is among the 10 most disabling mental health conditions worldwide, affecting about three in every 100 people — as many as one million Canadians.

Researchers at the Mathison Centre for Mental Health Research and Education/Hotchkiss Brain Institute at the Cumming School of Medicine have partnered with Alberta Health Services to develop an innovative, integrated clinical research program to address challenges in treating people with OCD. This program — the Calgary OCD Program — is testing new approaches to get the right treatment for the right person at the right time. The program builds upon the incredible research capacity and excellence that has been made possible by the transformational support provided to the Cumming School of Medicine by donors like the Hotchkiss family and Ron Mathison.

One of the new approaches being tested through the OCD Clinic is a ground-breaking discovery that is already providing relief to study participants — adults with treatment-resistant OCD. MRI-guided Focused Ultrasound (MRgFUS) uses ultrasound to target a specific region of the brain known to be involved in the genesis of OCD symptoms. This innovative research is led by neurosurgeon Dr. Zelma Kiss, MD, PhD, and psychiatrist Dr. Beverly Adams, MD.

“What’s unique about the MRgFUS protocol is that it’s safe and effective; we don’t have to open up the skull,” says Adams. “This procedure is done by heating a specific part of the brain to a certain temperature in an MR scanner, which makes it safe and cost effective. And most importantly, there seem to be few adverse side effects with this procedure.”

Adams adds that while preliminary positive results are not seen immediately, the progress and alleviation of symptoms become apparent over three months and even further at six months. And the relief for those who have undergone this procedure is life-changing: they no longer have the obsessive thoughts running over and over in their brain.

I have come a long way in the past year. Before the procedure, I was unable to participate in life for fear of being triggered . . . and I was severely limited in being able to leave the house. I am now able to go out to stores and the park regularly.

Calgary OCD Program study participant

“Our first study participant was unable to touch sharp objects,” describes Adams. “It meant she could not use knives for cooking or have them in the kitchen. She also had an obsession with Halloween-related objects and scary movies. Seeing these would trigger an obsessive thought process for her that would lead to compulsive rituals.”

These obsessions limited her ability to leave her house, and therefore impacted her quality of life.

“I have come a long way in the past year,” says the study participant. “Before the procedure, I was unable to participate in life for fear of being triggered by anything relating to harm. I could not use or be around knives or watch any TV shows or movies with weapons in them, and I was severely limited in being able to leave the house. I am now able to go out to stores and the park regularly, and I can enjoy and talk about The Witcher, one of my favorite video games.”

Early diagnosis and early intervention with medication and therapy are very important in treating OCD. Recognizing symptoms in childhood can be critical, because OCD can impact academic achievement, causing an incorrect diagnosis of a learning disability. But for treatment-resistant adults, this very specialized protocol and technique — currently in the early stages of clinical trials — is offering relief.

“My hope is that we can then offer this treatment to people with more moderate OCD conditions, thereby reducing their need for medications and avoiding unwanted side effects. It can also be difficult for patients to access therapy for psychological conditions. Regardless of what medical therapies are discovered, people with OCD will still need to learn long-term behavioural modification approaches as well. The goal of this novel treatment is to improve quality of life,” says Adams.

This research was funded by the Canada Foundation for Innovation and the Cumming Medical Research Fund, and private donors, including significant donations from the Rob McAlpine Legacy Initiative. To learn more about giving and how your support makes a difference, contact our giving team.

Dr. Beverly Adams, MD, is the senior associate Dean of Education at the Cumming School of Medicine, associate professor, Department of Psychiatry, and a member of The Mathison Centre for Mental Health Research and Education and the Hotchkiss Brain Institute. Dr. Zelma Kiss, MD, PhD, is a neurosurgeon, professor in the Department of Clinical Neurosciences at the Cumming School of Medicine, and a member of The Mathison Centre for Mental Health Research and Education and the Hotchkiss Brain Institute.

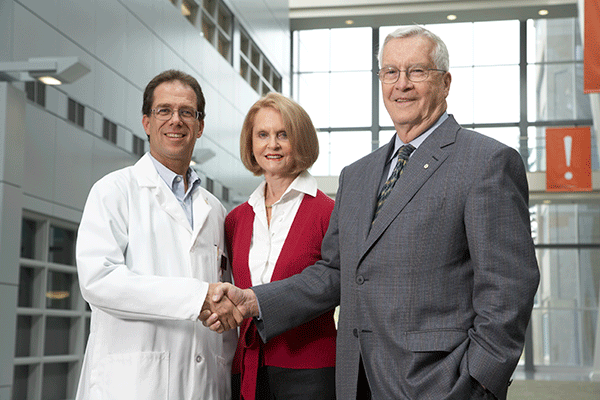

The Hotchkiss Brain Institute was enabled by a foundational gift from Harley and Rebecca Hotchkiss, shown above with Samuel Weiss (L), the founding director of the institute.

What Giving Gives Us

It wasn’t about having his name attached to it; Harley Hotchkiss had to be pushed to do that. I told him that the institute represents the best in science and medicine, but also in the best in citizenry and community. We had a chance to actually make a difference, so he lent his name to allow community and citizenry to meet science and medicine.

Samuel Weiss, PhD, founding director of the Hotchkiss Brain Institute (2004-2017)

The Hotchkiss Brain Institute was enabled by a foundational gift from the Hotchkiss family