March 5, 2018

UCalgary-led open-access medical curriculum recognized by United Nations

Making math flashcards to learn multiplication tables is straightforward enough. Likewise for the names of Canadian prime ministers. But what do you put on flashcards for family medicine?

That’s one of the questions a pan-Canadian group of family medicine educators grappled with over several years. With leadership from the Cumming School of Medicine (CSM) at the University of Calgary and the involvement of over 40 family medicine students and several residents, they worked together to develop a comprehensive collection of educational resources.

The result is the Shared Canadian Curriculum in Family Medicine (SHARC-FM), a free, open-access, national curriculum. It includes not just those point-of-care clinical flashcards for students to refer to as they look after patients, but also virtual patient cases, references and assessment tools, all aligned with the core topics in the family medicine curriculum.The University of Calgary's David Keegan, above, teaches with the Shared Canadian Curriculum in Family Medicine — a collaboration between medical schools across Canada to strengthen training of students.

The course and tools were recently recognized by the United Nations (UN) as a partner resource for medical students and educators throughout the world as part of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. The program will be showcased at the university’s Open Education Week March 5 to 9.

The highly organized clinical cards are a key component of the open-education resource.

Riley Brandt, University of Calgary

Exposure to a wide variety of patients

The project began more than a decade ago in 2006 when medical schools across the country were each creating their own online learning modules with minimal collaboration. At the same time accreditation standards changed, requiring medical schools to identify and track the types of patients that students were expected to see during each clerkship rotation. The goal was to ensure each student had broad exposure to the full range of patients and scenarios they would one day encounter, from paediatrics to pregnancy and palliative care.

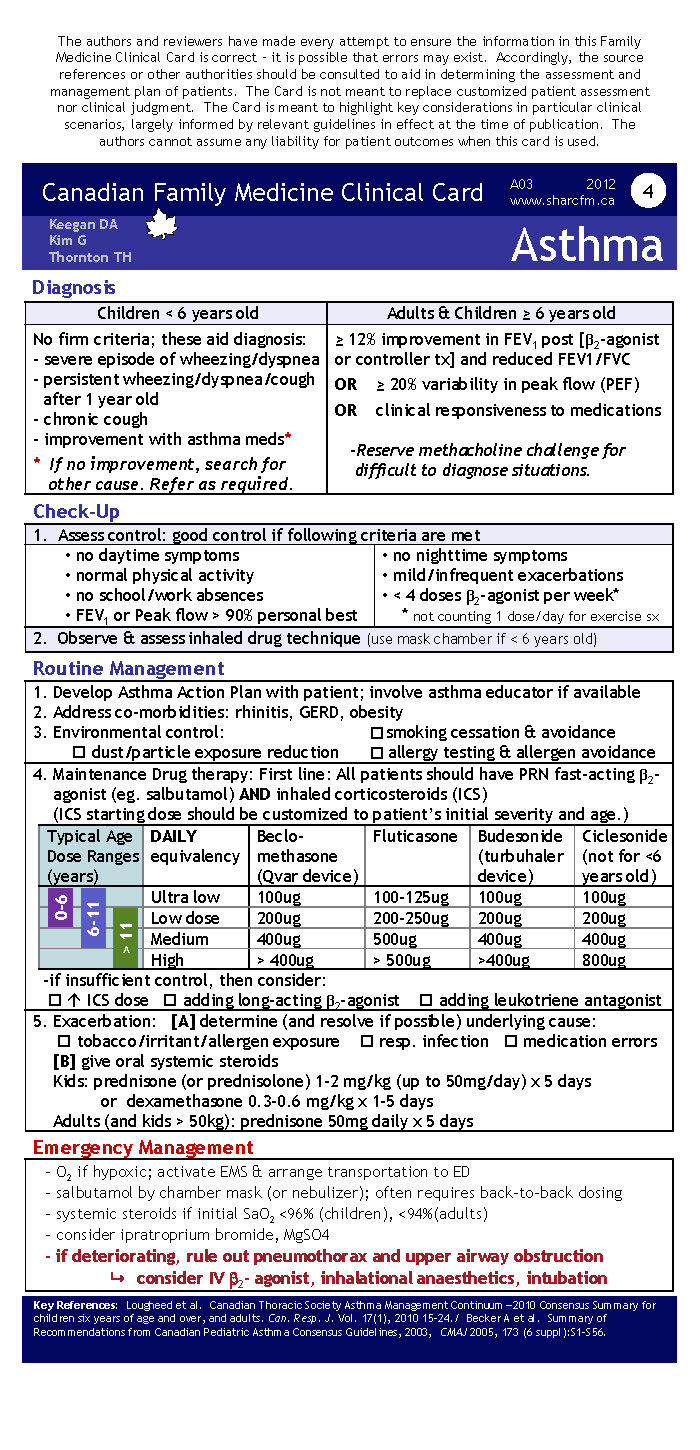

“We had to track whether each student encountered specific cases and scenarios during their clerkships,” says Dr. David Keegan, associate dean of faculty development and associate professor in the Department of Family Medicine in the CSM and founding lead/editor for SHARC-FM. “We needed to be assured that if they did not encounter a particular condition — like asthma — they would still have some kind of robust experience with it beyond book learning.”

Rather than working independently to create a resource to ensure well-rounded clerkships, Keegan led the charge on a national project involving all 17 Canadian medical schools. The Canadian Undergraduate Family Medicine Education Directors worked together to specify which experiences would be considered essential in a family medicine education, and how to offer students meaningful exposure to those topics.

“If you are overly ambitious with the topics, and you have to curate and create materials for each of them, that can become too daunting a task,” Keegan says. “We focused on the key set of clinical scenarios, the core, and by doing that it was more sustainable and wasn’t as big a mountain to climb.”

One of four asthma information cards in SHARC-FM family medicine curriculum.

SHARC-FM

Building shared curriculum around core competencies

Once the group had settled on core scenarios and their respective learning objectives, they found existing resources where they could — pointing students to reliable journal articles — and where there were gaps, they created resources. “We developed several types of resources,” Keegan says. “The most successful are the point-of-care clinical cards that students can have in their hands and refer to as they care for patients,” for example, the asthma clinical care card image at right.

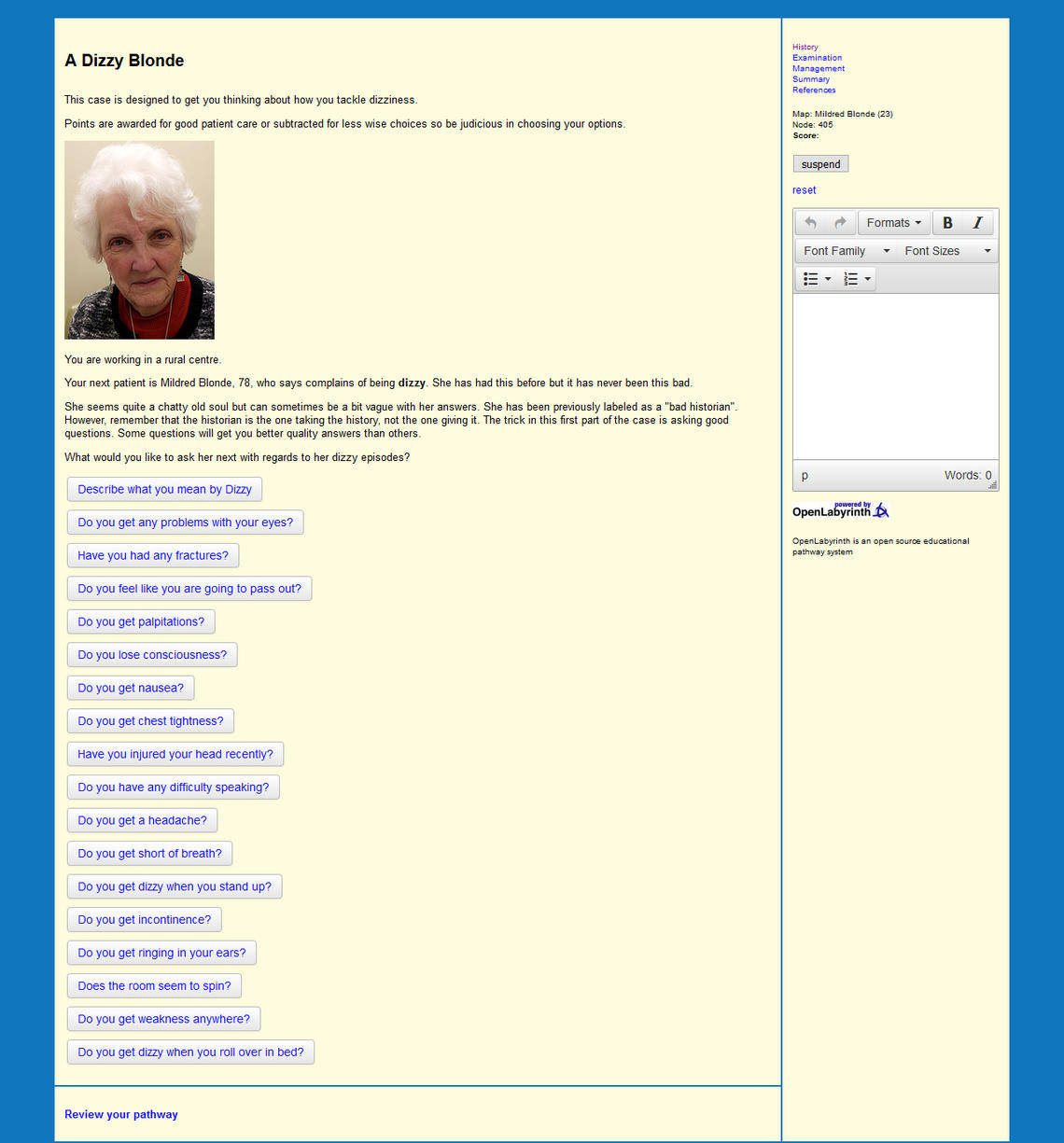

Like the practice of family medicine, the clinical scenarios are incredibly wide-ranging, from dizziness to back pain to fever. The open-access curriculum includes a list of objectives to be reached by the end of a clerkship, complete with references, virtual cases, paper cases, foundational knowledge, and the highly organized and densely packed clinical cards.

The manuscript describing the educational research behind the development of SHARC-FM, and the lessons learned from its development, was published in Canadian Family Physician.

“This national collaboration is a great example of creating an open education resource that can be shared globally to provide broad access to researched, peer-reviewed academic learning materials,” says Ykje Piera, open educational resources lead at UCalgary. It’s one of several open educational resources which will be featured at the Open Education Week Showcase March 8.

A dizziness case featuring 78-year-old Mildred, a virtual patient being treated in a rural centre.

SHARC-FM