|

|

| | Home | Intro | Tour(ism) | Montagnards | Society | Culture | Language | Images | Music | Library | Sakun | Links | !! Latest additions !! |

|

Clanship as process Anthropology text books define clans as "unilineal descent groups whose members are descended from a common ancestor ...[who] lived so far in the past that not all members of the clan can explain precisely how they are related to one another ...* (Bailey and Peoples 2002:133). This is a simplification in accordance with indigenous ideology. Clan membership is not in fact based solely upon kinship but can be achieved by the adoption of individuals and the merger of groups that share the idea, the metaphor, of unilineal descent. Conversely, supposed links may over time come to be ignored or disregarded. In such circumstances clans divide and their members are bound by new conventions relating to marriage, the tenure of capital (and especially land), and inheritance. The Sakun word səɗ, which means both seed and clan, expresses the ideology of descent. But at any one time clanship is a structure in process, one in which mergers and divisions are taking place at several scales. Unfortunately we lack evidence to provide a full account of historical changes in Sukur clanship but we can attempt to infer some characteristics of such changes from archival sources and our observations at Sukur in the period 1992-1996. |

|

Clanship, rights and history Clan membership is fundamental to the life of the Sukur as it bestows critical rights and obligations, specifying the range of potential marriage partners and giving access to the means of subsistence. In return one may be required to support other members of one's clan even in sometimes violent disputes, or in ceremonies such as Yawal that can make considerable demands on a person's resources. It is because of the importance of clanship that a great deal of Sukur history is encapsulated in the histories of individual clans. Since these refer primarily to themselves, the would-be historian is faced with the task of their integration and synthesis. |

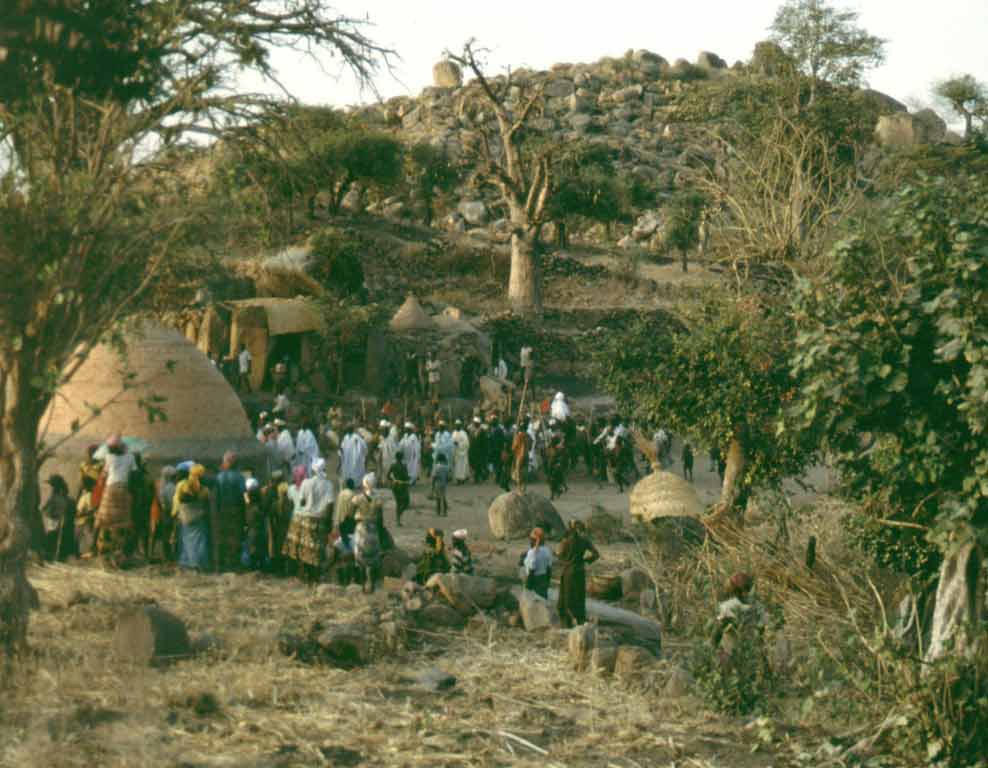

At the Yawal ceremony, the Dur clan celebrates itself and its holding

of the chietaincy. Here male members of the clan, the chief on a horse imported

for the occasion, process across the Patla.

At the Yawal ceremony, the Dur clan celebrates itself and its holding

of the chietaincy. Here male members of the clan, the chief on a horse imported

for the occasion, process across the Patla. |

|

The clans of Sukur and Damay in the 1930s

What is most striking about this table is that Shaw's listing is so nearly complete. Indeed his "omissions" are mainly due to the failure to differentiate clans that either share a praise name (e.g., Bakyang and Mədləŋ are subsumed under Habəga) or are otherwise closely linked and often not distinguished by the Sukur themselves (e.g., Gadə and Manjam). One other disagreement is worth noting. His 'Piltada' can only be the Kəmavuɗ. We suspect that a descriptive term, based on the root pətla meaning to break or smash, and which is used metaphorically, has been substituted for the name of the clan - but we are unaware of any incident that might explain why were described as trouble makers. In summary, Kulp's and Shaw's data, when compared with our 'final' listing of Sukur clans and praise names in the next section, demonstrate a remarkable continuity with the present, modified primarily by movement at a family level down onto the plains. This applies also to to Damay. |

|

Sukur clans and clan sections in the 1990s After presenting material on clans and sections, praise names, and clan and section origins in tabular form, we show how the interrelationships of clans and sections indicate a system in permanent flux. Clan histories are treated and a synthesis attempted on a separate page connected to each clan and group name in the table below by hyperlinks.

It is to be noted that with regard to origins, a higher proportion of clans now claim to have come from Gudur than was apparently the case in the early 1930s. Whether this is due to differences in data collection by observers or to a widening of the desire to attach one's ancestors to that prestigious magico-religious center is uncertain, but we suspect the latter. Clan sections: evidence of a system in flux In talking to Sukur about clanship three phrases are regularly repeated. Clans are exogamous and thus men of different clans "marry each others' daughters". The levirate is practiced within the clan, which is to say that if a man dies and his widow is willing, his brother - and potentially any clan brother - inherits his house and with it the responsibility for looking after his wife or wives and young children. Thus clan brothers "inherit each others' houses". Sukur differentiate between primary marriages, usually celebrated with considerable ceremony and never entirely dissolved, and secondary marriages that are both entered into and sometimes ended with little formality. (A woman's first marriage is her primary marriage; men can have more than one primary marriage partner.) A clan brother would never marry a woman whose primary marriage was with a clan brother so long as he was alive, nor can he marry a woman living in secondary marriage with a clan brother. (She would first have to leave her partner, marry a man of a different clan and then leave him.) Men of different clans are not subject to such restraints; they "marry each others' wives". Such are the norms, but as the table below indicates there is in fact considerable variation.

The sections of the Təvwa clan marry each other's daughters but in other ways behave as if they were the same clan. Perhaps the latitude allowed in seeking marriage partners can be attributed to the small numbers of smith/potters and the prohibition, now just beginning to weaken, against marriage between the smith/potter and farmer castes. A different pattern characterizes the Mədləŋ sections which behave as a single clan except in the matter of the levirate; they claim not to "inherit each others' houses". The reason for this is obscure and may in fact express what has happened rather than what should happen; if indeed there is a norm it may be connected with the possible smith/potter status of the ancestor of the ləiwaɗ section. Gadə and Ka-Ozha have the same pattern of behaviors but have different praise names. The Manjam, by which name the Ka-Ozha are known to many Sukur, take that name from a neighborhood in Guzka ward where they once lived. They are members of a trans-ethnic descent group that extends to Wula Kushiri where they retain the designation Ka-Ozha, the clan of the Tluwala rain maker. Although closely associated with Gadə, they have separate histories and titles, and it is clear that since they do not "inherit each others' houses" and have different praise names the two kin groups are not (as yet?) fully integrated as a clan.

In summary, although the structuring of society by clanship is fundamental element of social order, the clans of Sukur are not set in stone. A variety of political, historical, demographic, migratory and other factors are bringing about change and have acted in similar ways in the past. |