Feb. 8, 2018

Natalie Wood: Nothing can bring back the hour of Splendor in the Grass

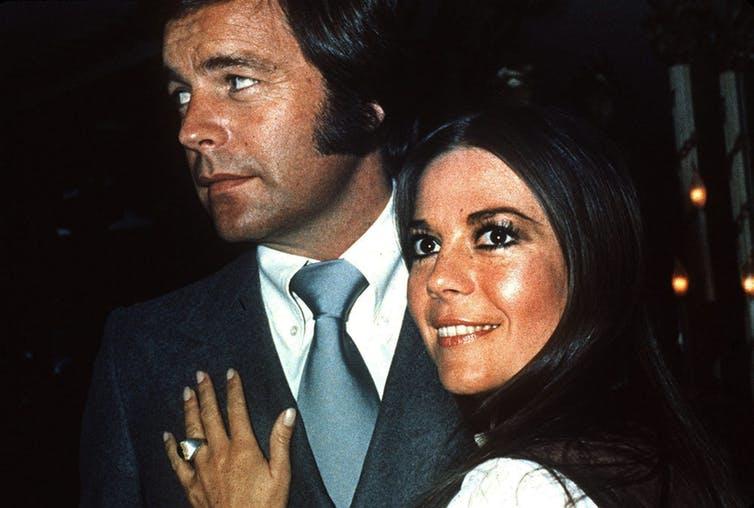

Robert Wagner appears with actress Natalie Wood.

AP Photo, File

The star system does brutal things to women (Good Housekeeping, 1962).

That prophetic statement from a magazine profile at the height of her fame encapsulates the legacy of Natalie Wood, the last Hollywood star of the studio system. This week, Wood returned to the headlines as Los Angeles County detectives appealed for more information regarding her “suspicious circumstances death.”

Wood haunts our collective cultural memory — mostly through lurid speculation on the circumstances of her drowning on Nov. 29, 1981. Did she drunkenly stumble off her yacht, The Splendour, or was she thrown in by her husband, matinee idol Robert Wagner? As soon as Wood’s body was recovered, the tabloids went into overdrive. Thomas Noguchi, the oft-described “coroner to the stars,” led the investigation and was eventually demoted in part for using the press to incite gossip and innuendo.

But the plot had already been set in motion, and the mystery surrounding the last moments of Wood’s life has cast a pall over her iconic career.

An actress for her era

Someday critics are going to realize that many of her films were not only good, but were remarkable testaments of both a certain time and a certain social condition in America (People, 1981).

Natalie Wood by Rebecca Sullivan.

Rebecca Sullivan

Those words were spoken at Wood’s funeral by journalist and friend Thomas Thompson. Already there was a frustration that Wood would not be remembered for her accomplished life but for a senseless death. She is neglected in critical appraisals of her greatest films: Judy in Rebel Without a Cause; Deanie in Splendor in the Grass; Maria in West Side Story.

In my book Natalie Wood, the first to focus on her career, I argue “Hollywood never really gave her the chance to be at the centre of her own narrative.” She was one of the most generous actors of her generation, who made the likes of James Dean, Warren Beatty and Robert Redford stars from the moment she gazed rapturously at them on screen. They did not return the favour.

Sexual social problem films

Our sexual conscience on the silver screen (Officiel/USA 1980).

It wasn’t until the end of her career that we could truly appreciate what she did for American cinema. Look up any of the sexual social problem films of the mid-twentieth century and chances are it will star Natalie Wood. We watched her grow from child to mother on screen.

A young Natalie Wood in Hollywood, Calif., with actress Jane Wyatt on this Oct. 26, 1949.

AP Photo

Her first star profile, in Motion Picture Magazine (1945), described her as a “six-year-old siren.” For the rest of her career, the press cast Wood as a “child-woman,” perpetually on the verge of self-destruction due to both her unrestrained passion and fierce ambition. Wood herself claimed that role left her “in emotional ruins,” trying to please everyone — family, friends, directors, fans.

That, I suggest, was the sexual script for women at the height of the sexual revolution. They must be sexually available yet servile to the men who desired them. Chaste and respectable, with the promise that violation would be secretly welcomed.

In the era of #MeToo, we can reflect on that no-win situation for women as the cinematic turning point when women’s sexual enlightenment came at the pleasure of men who used and abused them for their own personal and professional satisfaction. Directors often crossed Wood’s boundaries to extract a performance from her that left her “naked and gasping,” as Elia Kazan, her director on Splendor in the Grass told Newsweekin 1962. There is something too horrible to contemplate that five different times in her career, directors put her life at risk by drowning. She once remarked, “I’ve been terrified of the water ever since I was 12 … and yet it seems I’m forced to go into it on every movie that I make.”

The first time it happened, she was only ten years old. A rickety bridge collapsed over a raging river for a scene in The Green Promise. The cameras continued to roll as she struggled for her life. In Splendor in the Grass, Deanie attempts suicide at the reservoir. Wood recalled telling Kazan she was too scared to do the scene. Like Uma Thurman in Kill Bill Vol. 2, she asked for a stunt double only to have the director refuse. Instead, she said, “they threw me in, and had to get me out fast before I drowned.”

Missing women of Hollywood

What the world missed was one more portrait in this very very empty gallery of portraits of what women are really like at different stages in their lives (E! True Hollywood Story, 1997).

These words by actor/director Henry Jaglom ruefully remind us of his former lover’s lasting gift to cinema. No other actress encapsulates a generation of women struggling with rapidly changing sexual mores from childhood to death. Thompson wrote, six years before Wood’s death, “Hers was the familiar Hollywood story: Stardom, marriage, divorce, then downhill on Seconals, sycophants and depression. But Natalie finally said, ‘To hell with that script, I like beautiful endings.’”

In her final years, she represented herself as a happy, middle-aged wife and mother finally able to strike that elusive balance between career and family. She was returning to work, but good roles were hard to come by in the hypermasculine cinema of the seventies.

A 1981 file photo shows actress Natalie Wood.

AP Photo/File

To this day, Hollywood regards women in their forties as “old” and no longer worthy of storytelling. On film, they are relegated to be the silent, suffering companion of the man. Wood’s last starring role was just that: The estranged wife to a brilliant scientist who invades her memories in order to force a reconciliation.

The movie, Brainstorm, was completed without her. During a break in filming, Wood and Wagner took her co-star, Christopher Walken, on a cruise around Catalina Island, in Southern California. Her body was later retrieved in a cove about a mile away from their yacht.

The eternal ingénue

In its turbulence, uncertainty and confusion, life, Natalie Wood’s life, imitates art – the sad, lost, searching, lonely role she plays on the screen (Photoplay, 1962).

What little the public knows about the final moments of Wood’s life play like one of her movies. All too often, her character does not seize control of her destiny but merely recedes into the background, her final statement left unspoken, her acts of defiance stopped in their tracks.

In the stateroom of The Splendour, following a spree of binge drinking and pill popping, Wagner and Walken began an ugly argument over what Wood should be — family matron or leading lady actress. In the midst of the shouting, Wood exited, infuriated by the way these men ignored her as they fought violently for the right to define her.

What happened next is the stuff of conspiracy and intrigue, and the possibility that the truth will ever be known grows dimmer with every passing year. All we have left are her films, chronicles of women’s uneasy first steps into sexual independence; desperately seeking men who will celebrate them, not suppress them.

Wood did not survive this chapter in our culture’s story of women. But if we remember her for her life rather than her death, maybe we’ll get to those beautiful endings that women everywhere deserve.